ASN MA DEGREE SHOWS

•

•= it, they, he, she, آن

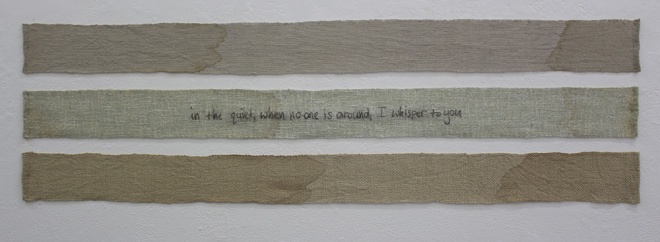

In telling •‘s story I should ask: who is •? or what is •? or where is •? This piece of text explores these questions by addressing and rephrasing these questions in the context of • itself. Thereby, the works mentioned in this text are not representative on their own but unpack processes within which •‘s story unfolds. I am neither the conductor nor the observer, but a dynamic relationship born out of the act of seeking •. I use the English language as a tool to write, and occasionally think in the Persian language. I expand my mind to think in both a second language and in a second world of •. I practice art to become with •.

“What you seek is seeking you” or “You are what you are seeking” Mevlana.

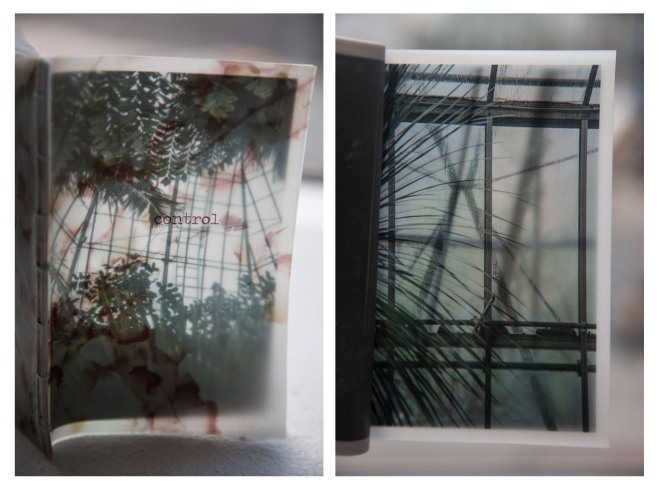

Voynich Manuscript

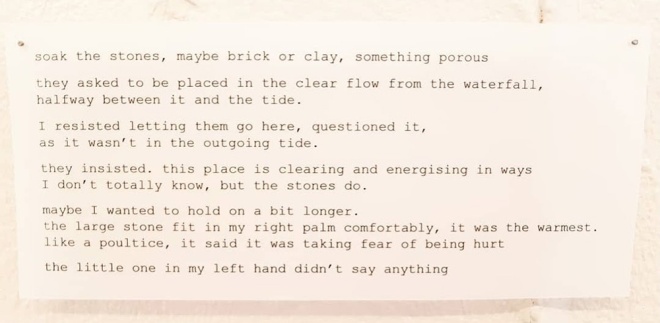

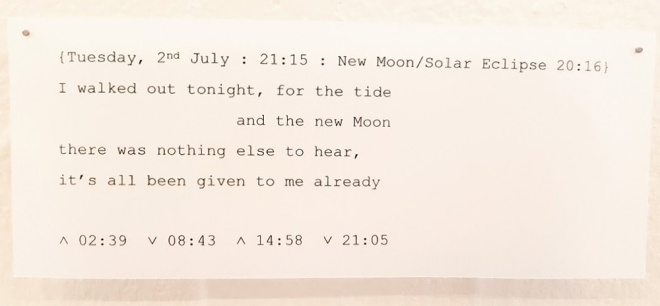

The search for • began early on with the “Collaboration with Audacity” which was the representation of a failure: the difficulty of representing the sense of a place within a gallery context. Images of the place were turned into sounds by manipulating their visual data. • became the difficulty of the task to transfer the experience of being present in a landscape to another place. This was explored and narrated in a field-trip to east coast of Scotland where thoughts and differences were washed away on the shoreline among rocks and creatures. The presence left space for • to transform into different definitions of time, place and persona.

[click here to play the sound]

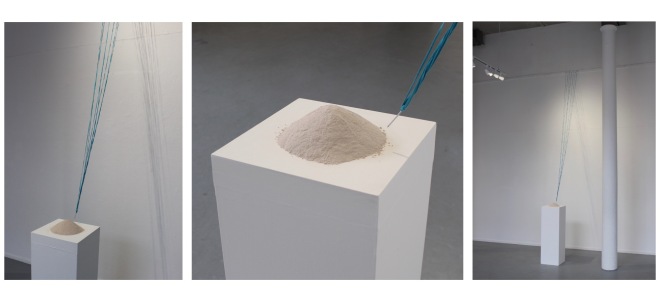

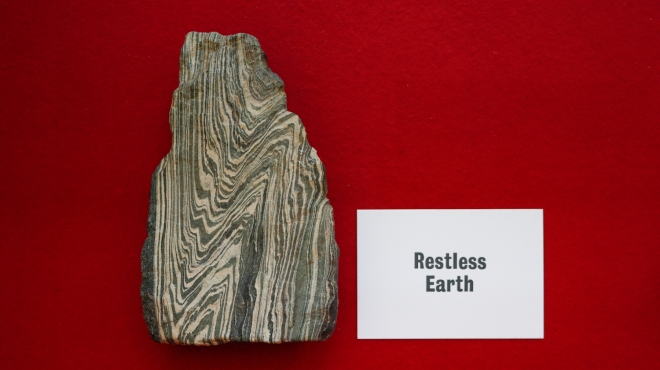

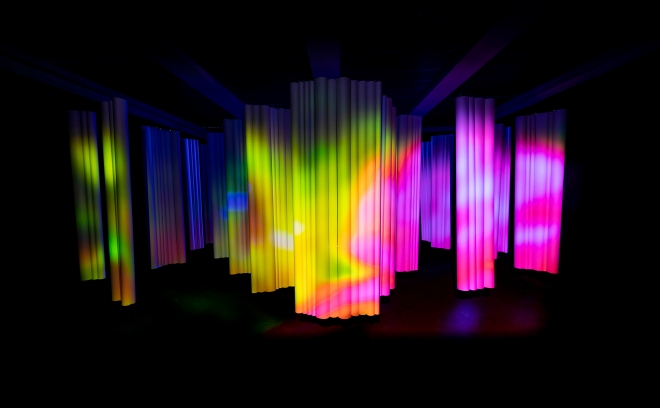

This transformation let • grow as a more complex form of exploration where I became a context for new conversations to form within. The physical and imaginative body that constituted me started to share life with • who formed connections between people of another history and land. The shared life was the process and exploration which represented a commonality. In “conversations”, a collective of photographs archiving the history of the Western Isles in Scotland are juxtaposed with a series of photographs from the current Iran, mostly taken in Hormuz island. Worlds, histories, cultures, artists, colours, shades, roots, rocks, soils and souls converse. Where is Iran and where is Scotland? The audience ask and answer in the game of juxtaposition. The conversation and commonality disturb the familiarity and brings about questions about politics of borders and information, the archeology of human-beings and what it takes to record this. A commonality that goes beyond differences, thus the challenging task of sharing “interests in common that are not the same interests” (Blaser & de la Cadena 2017) becomes possible.

“A connection at a level of the soul that goes deeper than superficial cultural differences; a connection simply by virtue of our underlying humanity.” Alastair McIntosh

“A connection at a level of the soul that goes deeper than superficial cultural differences; a connection simply by virtue of our underlying humanity.” Alastair McIntosh

The shared life soon formed a bond in a land of transformations and cross-livings: Wetlands. Lands of water or oceans of solid organic matters layered on top of one another throughout thousands of years (Mitsch & Gosselink 2007) Being “one of the most important ecosystems on Earth” (ibid. 3) they are known as “the kidneys of landscape” and “ecological supermarkets” (ibid.). “In the great scheme of things, the swampy environment of the Carboniferous period produced and preserved many of the fossil fuels on which our society now depends.” (ibid.) The complexity of these environments, their abundance in the new land I had migrated to and their “half-way” quality that couldn’t fit into categories and boundaries (ibid., p.30) easily was the life of • . Their calmness and marginalization weaved us together: two continents, two languages, two bodies of life together in one place. I became • and • became the landscape.

Spending time in wetlands connected me to people working in peatlands in the Flow Country, my friends in Iran and new collaborations to begin one of which was the Wetlands Sketches Project. The possibilities brought by the landscape connected me to on-going and ever-evolving becoming with •, whether present or absent. New ideas, new people, new beginnings, new endings, new failures. Together with Kate Foster the Wetlands Sketches Project invited people to share their incomplete ideas about wetlands art which was presented in a form of an audio-visual installation at Wetlands International Day 2019. The event was celebrating the presence of a single Siberian Crane (Grus leucogeranus) that takes a two-month journey of 5000 KM from Uvat in western Siberia to Fereydunkenar wetlands in Iran for the past few years. The crane who is the only remaining one to take this route has been called “Omid” by the locals which means hope in Persian. He showed up again in November 2018 after years of absence caused by his partner’s death. The locals celebrated his presence who brought omid (hope) with himself.

[Sound Installation – click here or on image to see full video]

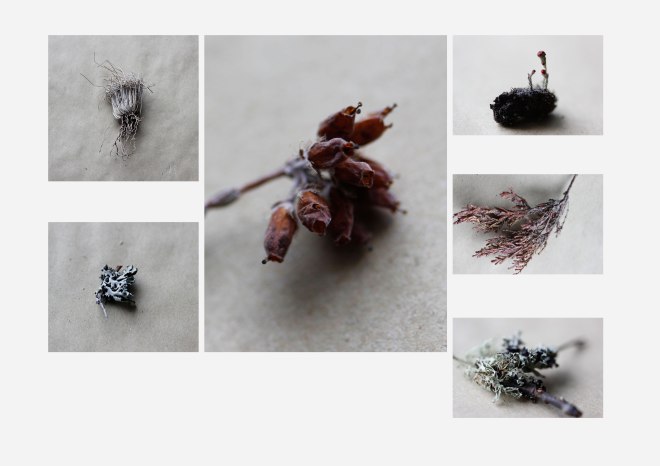

Siberian Crane

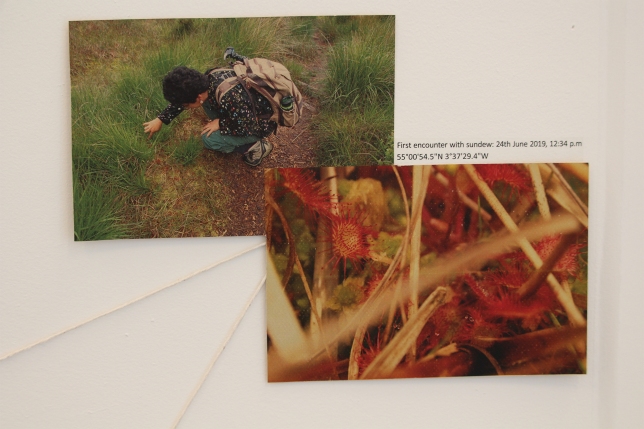

The research about the plant sundew (Drosera) was a turning point for an exploration in the absence of the case study. The “bubble world” (Tsing, 2015, p. 156) of •, called by humans, is Drosera or Sundew. I like Sundew more: “The Dewe of the Sonne” (Sundews n.d.). An expression used to connect dew with the sun. They used me, they drew me, they loved me (Enquist, 2016) and I became present. The presence of the others made me reach my sensors of attention into the air, and my limitations of my attention glitters in your eye beneath the sun (Darwin, 1875, pp. 1-14). The “bubble world” (Tsing, 2015, p. 156) of a human burst into a new world that challenged the premade categorizations and classifications. The plant grew in me and lived a new life. A text was written to describe the sundew’s world from its own point of view. An attempt to re-define what it means to be a scientist, an artist, a human or a plant.

The shared life of • found a new kind of presence. • took various forms and found different ways to become present through absence. The absence of others gave voice to solo travelers and migrators such as me or Omid. “Absence” represented a presence in a forest, a gathering of people and a lone wolf. The absence of • became present both in the field and in the gallery.

• becomes present in the process of thinking about • and • become present in •‘s physical absence. An ongoing attempt to spend time with the plant sundew is the new work. An ongoing attempt to spend time with the human Pantea Armanfar is the new work. The journey to look for each other began in summer 2019 around Scottish wetlands and first came to happen in Kirkconnel Flow in Dumfries, Scotland. Soon after • reunited in peatlands in Scottish Borders area, Red Moss and Knowetops Loch. Their business, life, love and death crossed one another. The shared life brought about possibilities beyond one another.

Pantea Armanfar and the sundew share the life of • . • proposes an imaginary landscape where urban life weaves together with wetlands. They encourage listening and being in a landscape that is fascinating and subtle, but not orderly and quiet. A proposal for an imagined place, time and society to be sought. • becomes present in my response to reaching, thinking and spending time with • .

• is “آن” and thinks as “آن“ .”آن” stands for the Persian article for “he/she/it/them/you”. As Mevlana puts it “هر آنچه در جستن آنی آنی” : what you seek is seeking you or you are what you are seeking or whatever “آن” you are seeking to be, you are “آن”. •‘s livability is dependent not on •‘s knowledge of •, but on the diversity of ways in which • can think of • or possibly live •. In this sense, • unlearns, • unseeks, • undoes, • stops knowing.

Pantea Armanfar is an artist working with experimental documentary, analogue photography and field recording to explore new ways of telling stories. She studies themes of the environment, immigration and wetlands.

Bibliography:

Books

Allaby, M., 2006. A Dictionary of Plant Sciences 2nd ed., Oxford University Press (Oxford Reference Online), accessed 24 March 2019, DOI: 10.1093/acref/9780198608912.001.0001.

Cambridge, G 2000, Nothing but heather!’: Scottish nature in poems, photographs and prose, Luath Press Ltd., Edinburgh.

Darwin, C., 1875. Insectivorous Plants, Place of publication not identified: publisher not identified.

Mitsch, W.J. & Gosselink, J.G., 2007. Wetlands, 4th edn, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey.

Tsing, A.L., 2015. The mushroom at the end of the world: on the possibility of life in capitalist ruins, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Webpages

Enquist, S., ‘Charles Darwin’s Love Affair: The Sundew to his Moondew’, The recovery discovery, 19 May 2016, accessed 10 March 2019, http://blogs.evergreen.edu/pim-group1/charles-darwins-love- affair/

Sundews n.d., Carnivorous Plant Resource, Accessed 10 March 2019, https:// carnivorousplantresource.com/the-plants/sundews/

Images

Voynich Manuscript 2014, Yale University Library, accessed 24 March 2019, http://beinecke1.library.yale.edu/download/Voynich-New/

Siberian Crane ‘Omid’ returns to Iran brings hope, TehranTimes, 1 December 2018, accessed 20 July 2019, https://www.tehrantimes.com/news/430098/Siberian-crane-Omid-returns-to-Iran-brings- hope

Collaboration: Periparus Ater charts the birds’ movements in a series of drawings. These maps are a meditation on avian time.

Collaboration: Periparus Ater charts the birds’ movements in a series of drawings. These maps are a meditation on avian time.

In here/there, Tzu-Yun Liang asks us to consider our position as humans within what we understand as ‘nature’.

In here/there, Tzu-Yun Liang asks us to consider our position as humans within what we understand as ‘nature’.

![[3]postcard.front-01](https://asnse.files.wordpress.com/2019/11/3postcard.front-01.jpg?w=610&h=433)